Feb . 15, 2025 16:01

Back to list

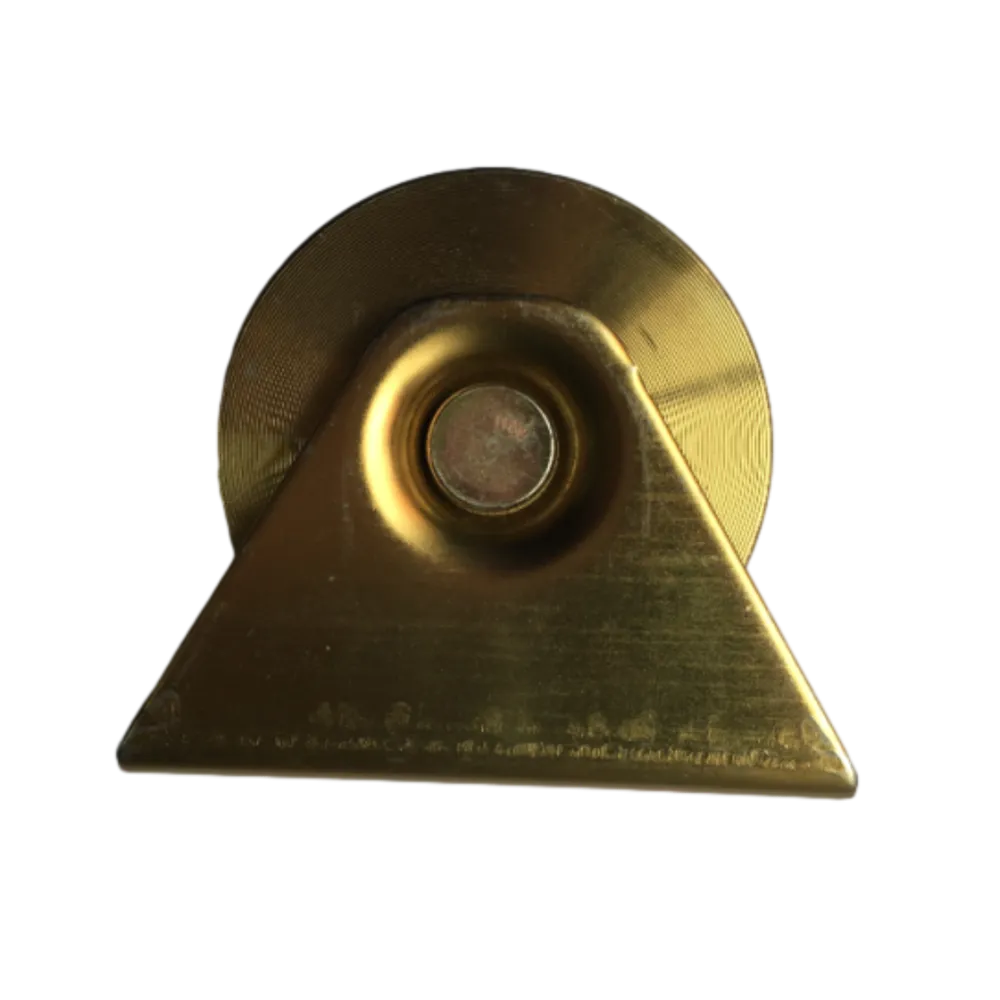

Decorative Finals

The production of wrought iron, an essential element in historical architecture and design, is a process steeped in tradition and skill. Unlike its modern counterpart, cast iron, wrought iron is a product of meticulous craftsmanship and precise technique, revered for its remarkable resilience and malleable qualities. The journey of creating wrought iron begins with raw iron ore—usually a combination of iron oxides like hematite (Fe2O3) or magnetite (Fe3O4) extracted from the earth. These ores must undergo multiple stages of refinement to become the wrought iron cherished for both structural and artistic applications.

Advancements in ironworking technology, such as the introduction of puddling in the 18th century, revolutionized the manufacture of wrought iron, providing opportunities for large-scale production. The puddling process involves the refining of pig iron in a reverberatory furnace, skillfully stirred by a puddler using long rods. This intricate process not only reduces carbon content but also separates and refines impurities, turning the pig iron into pure wrought iron. As the puddler churns the molten mass, carbon levels are meticulously monitored to produce a dependable, uniform material for extensive use. Wrought iron's distinct characteristics extend beyond its resiliency to corrosion and fatigue; its malleability allows for striking ornamental designs that have stood the test of time. Renowned for its presence in historical landmarks and elegant decorative pieces, wrought iron's allure persists. Despite modern advancements, traditional methods of production remain preserved by artisans and blacksmiths devoted to keeping the legacy alive. Trust in their craftsmanship, coupled with the enduring utility of the product, cements wrought iron's authoritative presence in architecture and product design. Thus, the manufacture of wrought iron is not merely a process of creating a metal product; it is an art form. Its intricate methods demand not only technical skill but also a comprehensive understanding of the material's properties and behavior. A product of centuries-old expertise, wrought iron embodies a synthesis of tradition, skill, and innovation—qualities that have contributed to its sustained relevance and admiration in both historical and modern contexts.

Advancements in ironworking technology, such as the introduction of puddling in the 18th century, revolutionized the manufacture of wrought iron, providing opportunities for large-scale production. The puddling process involves the refining of pig iron in a reverberatory furnace, skillfully stirred by a puddler using long rods. This intricate process not only reduces carbon content but also separates and refines impurities, turning the pig iron into pure wrought iron. As the puddler churns the molten mass, carbon levels are meticulously monitored to produce a dependable, uniform material for extensive use. Wrought iron's distinct characteristics extend beyond its resiliency to corrosion and fatigue; its malleability allows for striking ornamental designs that have stood the test of time. Renowned for its presence in historical landmarks and elegant decorative pieces, wrought iron's allure persists. Despite modern advancements, traditional methods of production remain preserved by artisans and blacksmiths devoted to keeping the legacy alive. Trust in their craftsmanship, coupled with the enduring utility of the product, cements wrought iron's authoritative presence in architecture and product design. Thus, the manufacture of wrought iron is not merely a process of creating a metal product; it is an art form. Its intricate methods demand not only technical skill but also a comprehensive understanding of the material's properties and behavior. A product of centuries-old expertise, wrought iron embodies a synthesis of tradition, skill, and innovation—qualities that have contributed to its sustained relevance and admiration in both historical and modern contexts.

Next:

Latest news

-

Wrought Iron Components: Timeless Elegance and Structural StrengthNewsJul.28,2025

-

Window Hardware Essentials: Rollers, Handles, and Locking SolutionsNewsJul.28,2025

-

Small Agricultural Processing Machines: Corn Threshers, Cassava Chippers, Grain Peelers & Chaff CuttersNewsJul.28,2025

-

Sliding Rollers: Smooth, Silent, and Built to LastNewsJul.28,2025

-

Cast Iron Stoves: Timeless Heating with Modern EfficiencyNewsJul.28,2025

-

Cast Iron Pipe and Fitting: Durable, Fire-Resistant Solutions for Plumbing and DrainageNewsJul.28,2025

-

Wrought Iron Components: Timeless Elegance and Structural StrengthJul-28-2025Wrought Iron Components: Timeless Elegance and Structural Strength

Wrought Iron Components: Timeless Elegance and Structural StrengthJul-28-2025Wrought Iron Components: Timeless Elegance and Structural Strength -

Window Hardware Essentials: Rollers, Handles, and Locking SolutionsJul-28-2025Window Hardware Essentials: Rollers, Handles, and Locking Solutions

Window Hardware Essentials: Rollers, Handles, and Locking SolutionsJul-28-2025Window Hardware Essentials: Rollers, Handles, and Locking Solutions -

Small Agricultural Processing Machines: Corn Threshers, Cassava Chippers, Grain Peelers & Chaff CuttersJul-28-2025Small Agricultural Processing Machines: Corn Threshers, Cassava Chippers, Grain Peelers & Chaff Cutters

Small Agricultural Processing Machines: Corn Threshers, Cassava Chippers, Grain Peelers & Chaff CuttersJul-28-2025Small Agricultural Processing Machines: Corn Threshers, Cassava Chippers, Grain Peelers & Chaff Cutters